Mason Spirit Magazine

Fall 2023 edition out now!

Flip through the issue on Issuu or via accessible PDF

Our award-winning faculty is dedicated to tackling the grand challenges of our time, which include issues surrounding sustainability. That dedication can be seen anywhere you set foot on a Mason campus, with our nearly 1,000 acres of land, waterways, forests, and buildings being used as a dynamic Living Lab for hands-on applied environmental research.

@ Mason

- April 5, 2024

- November 30, 2023

- November 8, 2023

- October 30, 2023

- October 24, 2023

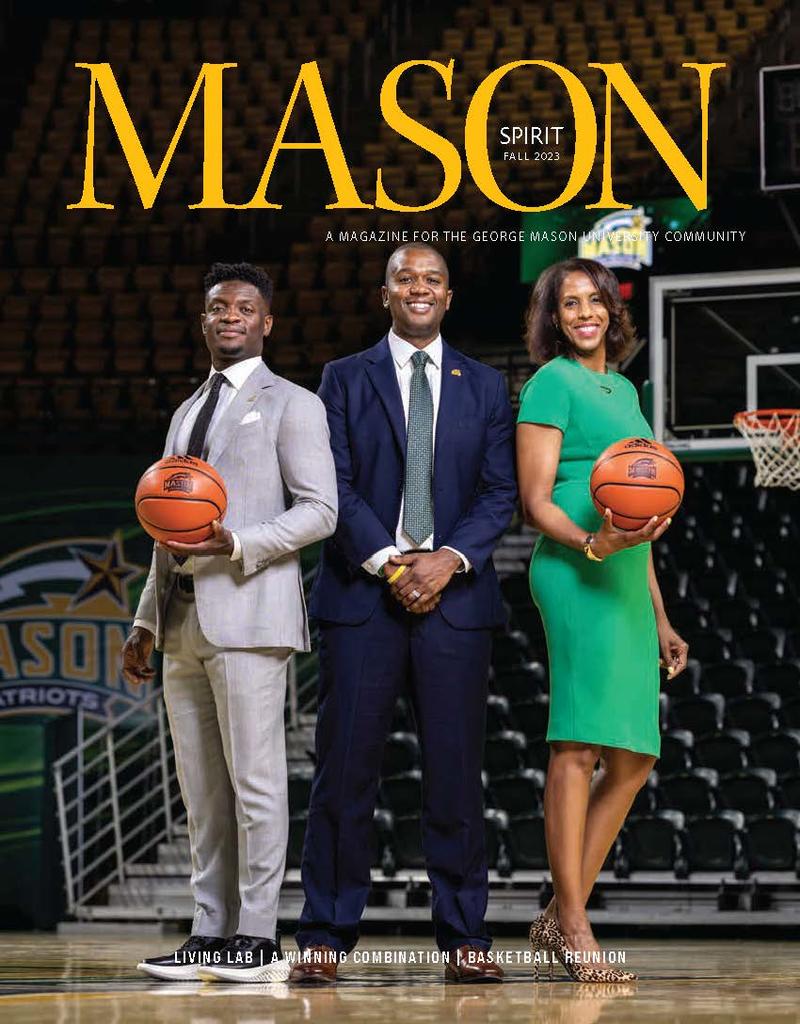

A Winning Combination

With dynamic new leadership and some Final Four nostalgia, the Mason Nation looks forward to another basketball season. We took the time to talk with the individuals leading our teams to victory.

Left to Right: Tony Skinn, Head Coach, Men's Basketball, Marvin Lewis, Assistant Vice President and Director of Intercollegiate Athletics and Vanessa Blair-Lewis, Head Coach, Women's Basketball

Green Leaf courses make sustainability a part of Mason's curriculum

Green isn’t just a school color at George Mason University. At Mason, “green” is way of life, and sustainability is central to the university’s mission. One of the ways Mason is doing this work is with Green Leaf courses, which are designed to help to raise environmental awareness while providing students with a comprehensive knowledge of their local and global environment.

Profiles

- April 5, 2024

- March 18, 2024

- November 8, 2023

- November 7, 2023

- November 7, 2023

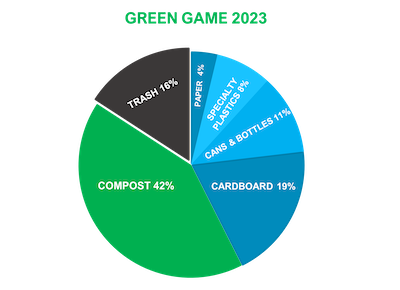

Green Game competition results are in

As a result, collectively, the Mason Nation has kept more than 200 million single-use plastic containers out of landfills and prevented the release of 29,108 metric tons equivalent of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, equal to avoiding the annual emissions from 6,128 cars.

Did you know three members of the 2006 Final Four basketball team now work on campus? And their presence is drawing more basketball alumni back to Fairfax.

Inquiring Minds

- November 7, 2023

- October 16, 2023

- October 12, 2023

- October 11, 2023

- August 9, 2023

Mason Korea launched in Songdo, South Korea, in March 2014, as part of the Incheon Global Campus.

Mason Spirit is published three times a year by the Office of University Branding and the Office of Advancement and Alumni Relations. Our print edition includes features such as class notes, faculty and alumni publications, letters to the editor, and more. Print copies are mailed to alumni, donors, and other friends of the university. If you have any questions about the magazine, please email us.